A back of the envelope case for load-shifting

A recurring question I ask myself is:

How much carbon savings can one actually achieve by load shifting e.g. an electric car charge?

Load shifting electric car charges or smart charging refers to the act of using an external signal (price, carbon intensity) for optimising the decision of when and how much to charge. There is no doubt that, even without carbon-aware smart charging, switching from a combustion engine car to an electric vehicle is beneficial in terms of greenhouse gas emissions [1].

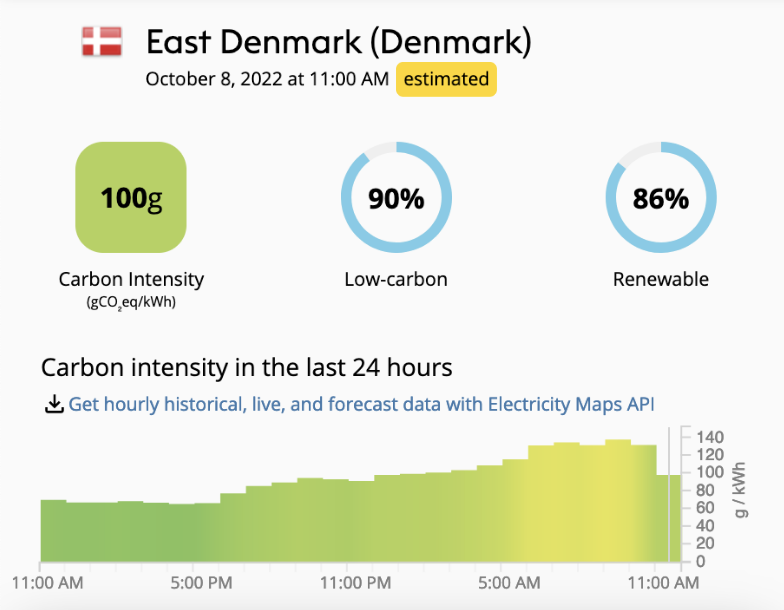

Furthermore, as more and more variable renewable electricity sources are integrated into the grid, its carbon intensity will display a higher variability. See below for a typical day in Sjælland, Denmark. The carbon intensity of the grid goes from around 60 gCO2eq/kWh to more than 130 gCO2eq/kWh (more than X2!) in a matter of hours.

This variability opens up the possibility to be leveraged for optimising any carbon-intensive electric activity with some level of flexibility. Electric car charges are one of the best example of this. Hence, my original question, how much benefit can we actually hope to get? And how much better can we make electric vehicles?

To do this, I’ll use a back of the envelope optimisation procedure in a simplified scenario.

Use case

Let’s stay in Eastern Denmark, and look at the example of Mette. Let’s say that she is an eco-conscious engineer that works for Novo Nordisk. Every day, she has to commute from her cozy apartment in central Copenhagen to Målov, where the company has production facilities. She drives a Tesla model 3 back and forth, for a total of around 70 km per day. She usually makes sure that her car is plugged in after she’s done putting her kids to bed, and walking her dog. Overall, that means that the car is plugged in between 00:00 an 07:00 every day.

The modelling

We will rely on the following assumptions, which should correspond to standard values for a Tesla model 3 [2]:

- Total battery capacity: 50 kWh

- Maximal charging power: 11 kW (assuming home charger, not fast charger)

- Daily energy consumption: 11.154 kWh (City/Highway combined drive cycle, in cold to mild climate for 70 km per day)

- Optimisation window: 48 hours (She would have access to 48h ahead forecasted carbon intensity)

Mette likes the safety of knowing that at the end of the optimisation window she will have a full battery. Physically, it’s also impossible to charge more after a day than what was consumed.

Naive charging

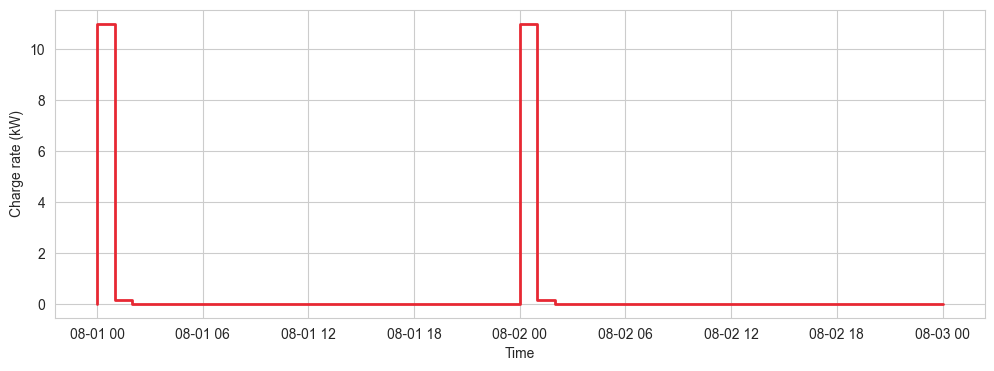

In the naive scenario, the car is plugged and charges at full power until it is fully charged.

The daily energy consumption being 11.154 kWh, it takes 1.02 hours to charge the car every day.

Smart charging

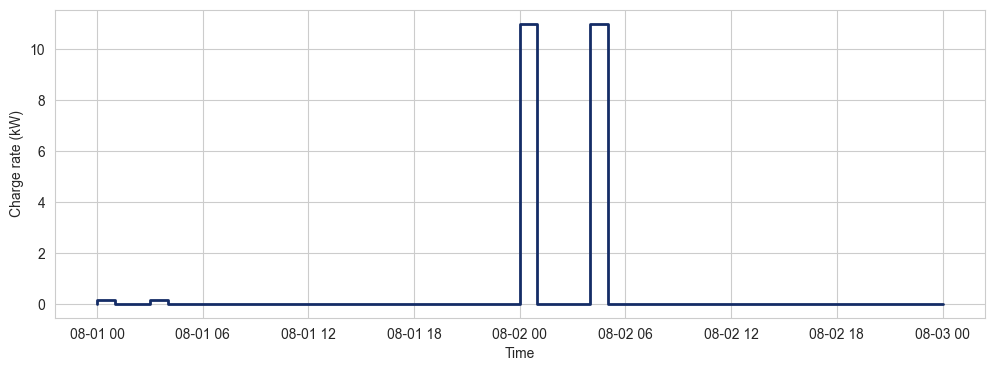

In the smart charging scenario, a simple optimisation algorithm is used to find the optimal charge times and power. It could potentially result in something like below.

The problem we are trying to optimise can be expressed in the standard form as:

\[\begin{aligned} \min_{x} & \;\;\;\mathbf{c}^T \mathbf{x} \\ \text{s.t.} & \;\;\;\mathbf{A}_{ub}\mathbf{x} \leq \mathbf{b}_{ub}\\ & \;\;\;\mathbf{A}_{eq}\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{b}_{eq}\\ & 0 \leq x_i \leq P_{\text{max}}, \quad i = 1, \dots, n \end{aligned}\]With \(E_d = 11.154\) (kWh) the daily energy usage, we have:

- \(\mathbf{x}\) is the vector of decision variables. Here, \(x_i\) represents the amount of energy charged at hour \(i\).

- \(\mathbf{c}\) is the vector of cost coefficients. Here, \(c_i\) represents the carbon intensity of the grid at hour \(i\).

- \(\mathbf{A}_{ub}\) is the matrix of upper bound constraints and \(\mathbf{b}_{ub}\) is the vector of upper bound constraints. Here, \(\mathbf{A}_{ub}\) and \(\mathbf{b}_{ub}\) are used to express the constraint of not being able to charge more than what was consumed.

with \(\mathbf{L}\) being the lower triangular matrix of ones and \(\mathbf{J}\) being the matrix of ones.

- \(\mathbf{A}_{eq}\) is the matrix of equality constraints and \(\mathbf{b}_{eq}\) is the vector of equality constraints. Here, \(\mathbf{A}_{eq}\) and \(\mathbf{b}_{eq}\) are used to express the constraint of having a full battery at the end of the optimisation window.

- \(P_{\text{max}}\) is the maximal charging power.

This linear optimisation problem can directly be solved by simple solvers.

Results

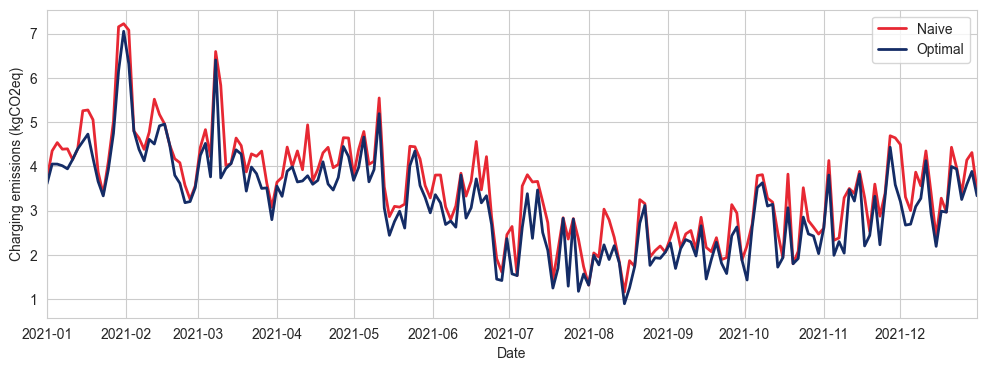

Overall, and reassuringly, we can see below that the daily emissions are lower for the smart charging scenario.

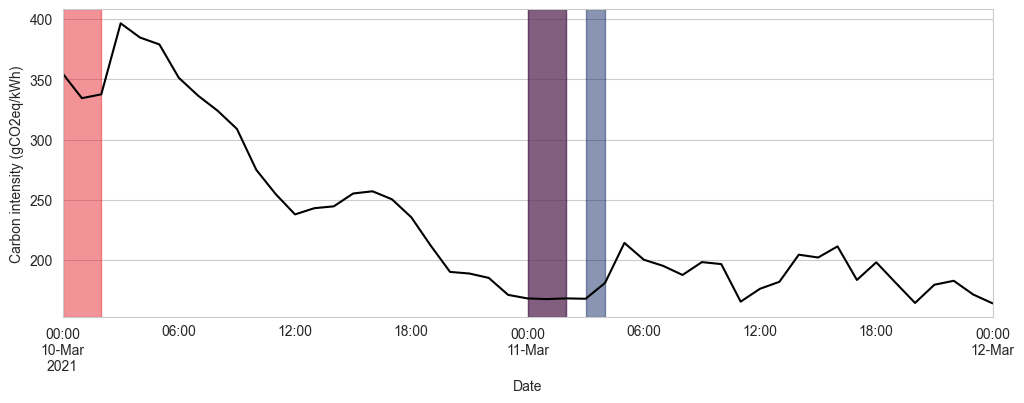

Looking at a specific day, we see what we would expect. Below highlights the selected charging times in both scenarii. For that specific two-day window, the second day has much lower carbon intensity, and the algorithm correctly tells our dear Mette to only charge during the second night.

Overall, this simple back of the envelope optimisation strategy leads to 66 kg of CO2 saved per year. That amounts to a 10% reduction of total emissions related to car charging.

| Naive | Optimal | |

|---|---|---|

| Total emissions (kgCOeq) | 643 | 577 |

In practice, this very simple modelling simply amounts to selecting the hours with the lowest carbon intensity in the optimisation window and charging as much as possible during these hours. This simplistic formulation of the problem might seem overly complex, and it is, but could be expanded with more realistic constraints.

For example, the behaviour of Mette could be different on weekends, and she might allow for greater flexibility than what we did.

Finally, orders of magnitude are important to keep in mind when considering how useful it would be in practice to roll out smart charging. These 66 kg of greenhouse gas saved are important as they are very much a low-hanging fruit. They nevertheless are only a fraction of what Mette would emit flying to Canada for her holidays, thinking that her ecoconscious behaviour compensates for her flying.

Thanks for reading!

You can find the code I wrote for this calculation here.

References

- [1] EPA

- [2] EV database